Accessibility is a word that has been thrown around a lot recently, but I find that even people who believe in making a space accessible may not be prepared to put in the work to do so. This is especially true in situations which operate within a system that is inherently inaccessible. I would like to outline the day of a grade 9 student in high school to show all the different ways in which the school system is inaccessible, and different ways that different educators and advocates could accommodate and include this student. However, because of the roots of the education system in a privileged, patriarchal, capitalist system, there are some inherent issues that cannot be addressed by individuals, and instead must be changed on a systemic level. For the purpose of this exercise, our student has three conditions which must be accommodated: Auditory Processing Disorder (APD), dyslexia, and chronic pain.

The day starts with an alarm at 6:30am, waking up our student in the middle of a REM cycle, making them groggy and disoriented. They have been stressed at school recently, making their pain worse, which prevents them from getting a good night’s sleep. They are tired and drained before the day even starts, which makes their pain even worse. They take their morning medication, but because of the pain, they are unable to eat breakfast. The medication is supposed to be taken with food, but because of their dyslexia, they haven’t been able to do research to find out how important that part is. Having skipped breakfast before, they figure it’s fine, so they ignore their abdominal cramps for the rest of the morning.

Because of the bad sleep, they are running behind in their morning routine. Their mom asks if they want a ride to school, but because of their undiagnosed APD, they only hear “get to school before the bell rings.” Most times they only hear part of a sentence, even less when they’re tired, and they are used to using their best guess to fill in the blanks. They misinterpret the offer for a reminder to get to school on time, and assure their mother that they’re fine, and head off to the bus.

It’s a later bus than usual this morning, busier because of rush hour and therefore there are no seats. Nervous to speak up and unable to hear properly on the crowded bus, the student chooses to stand. This increases their pain. The bus ride is short, but they still have to carefully keep track of which stop they’re at. They won’t be able to understand the stop announcements, because it sounds like a garbled mess, but it’s also not easy to read the font on the bus’s stop reader because it’s not dyslexia friendly. They focus so hard on catching the stop for their school that they miss a classmate calling out to them. This is not the first time this has happened. Our student doesn’t know what APD is, and assumes that everyone experiences large gaps in auditory understanding. Because of this, they have very few friends, and usually feel isolated.

They arrive late for class. The teacher stops her lecture to ask why the student can’t seem to arrive on time. Already stressed from the morning, the student simply can’t understand the words, and goes silently to their seat. This makes the teacher think that they are being intentionally disrespectful. This is not the first time this has happened. The teachers know about our student’s dyslexia, but they are just beginning to get tested for their chronic pain, and it’s very difficult to diagnose APD when hardly anyone even knows that it exists. All the teachers think our student is distracted and lazy, because they have an IEP to address their dyslexia, so why aren’t they even trying?

The student can barely follow along with the lecture slides, and though they get fill-in-the-blank notes because of their dyslexia, they still miss about half the words due to the combination of poor font choice on the slides, inability to understand the teacher properly, and being overtired and distracted from the pain. It’s impossible to follow along in group discussion afterwards, so they don’t participate. They get irritated looks from the teacher and know that other students are whispering about how weird they are. They leave the class feeling discouraged.

Second class of the day is P.E., our student’s least favourite class. No one believes them when they say they’re too sore to participate, and the teacher tells them to suck it up. They’re already close to failing the course. They come in last on the warmup run, which makes other students mock them. They can’t hear the teacher’s instructions during basketball drills. The teacher is the next to mock them and tells them they need to shape up or they’ll never succeed in life. The student stays in the locker room long after everyone else has left. They don’t feel like eating lunch today, either.

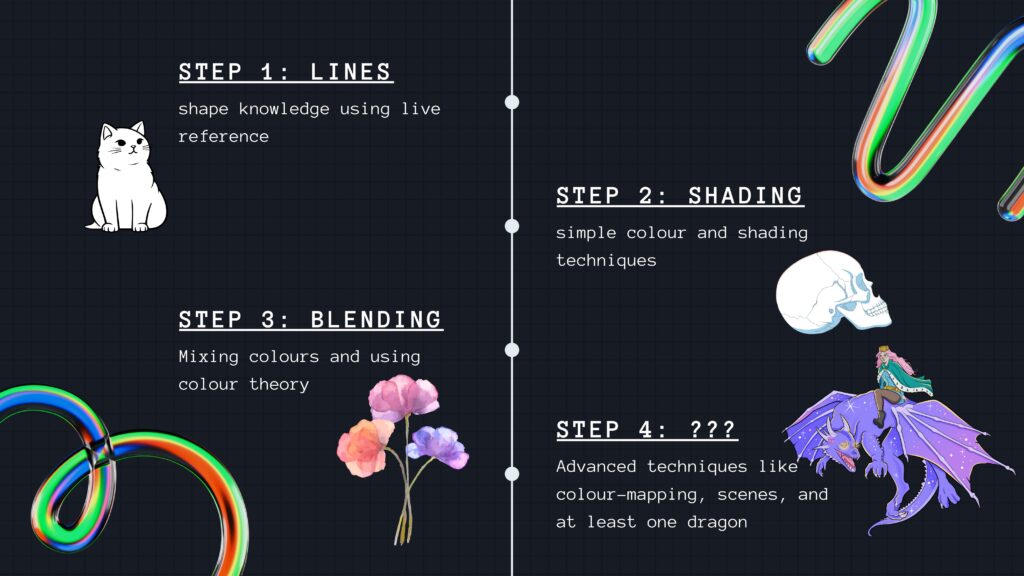

After lunch break is over, they can barely concentrate in their favourite class. Their art teacher asks each of her students each day how they’re feeling. She and our student both know a little bit of American Sign Language, so she uses it to supplement her questions. It works, even if neither of them know why. Our student answers that they’re fine. They don’t want to get into it right now. The teacher introduces todays lesson, then sets them off to work. She lets them complete each project however they want so long as it fits into the learning goals she sets out. Our student had such a great idea yesterday about what they could do for this one. Because of the day they’ve had so far, they don’t have the motivation to start.

At the end of art class, our student goes to their Inclusion Support Teacher (IST), who is their case manager and the one creating their IEP. They’re almost in tears. They beg to be allowed to go home. The IST is sympathetic, but this is a grade 9 student near the beginning of the year. They’re relatively new to the school, so without a strong relationship, the IST relies mostly on notes from middle school to figure out what’s really going on. The notes from middle school describe a student who doesn’t pay attention in class, doesn’t participate in class work or group projects, and tries to get out of school as often as possible. The IST tells the student they have to stick it out for one more class. As the student leaves, the IST writes down a note to add a behavioural issue to the student’s case file.

Our student skips the last block of the day and hide out in the library instead. That’s where the principal finds them, crying in the corner as they try to get some homework done. They’re brought in for a chat. The principal tries his best to figure out what’s going on, but the student is too distressed to be able to understand anything he’s saying. They aren’t given detention, but the principal calls their parents. Their mother is frustrated at having to leave work early yet again to pick up her child. She’s been getting criticism from her boss for doing so, and she doesn’t understand why her child is acting out this way all the time. The student doesn’t answer their mother’s angry questions on the ride home.

The student goes to bed without eating that day. None of their homework is done, and they’re so exhausted that no matter how much sleep they get, it will be even worse tomorrow. They’re planning on skipping at least the first two classes, maybe more, because the thought of facing the criticism of the teachers, hostility from their peers, and struggle of keeping up in the classes is all just too much. They feel useless, worthless, and alone. They don’t know what’s wrong with them, or why they act this way. They don’t know what to do.

This student may seem like an extreme case, but they are constructed from the experiences of many neurodivergent and disabled students I’ve spoken with about their own high school experiences. Some of those experiences were my own. There are so many little things that build up more and more until school itself feels like an inaccessible, insurmountable obstacle. Even if they do well in high school, university is much the same, but with even less support. I know more than a dozen peers who dropped out of university, not because of the material itself, but because they were not getting the accommodations they needed – the accommodations which could be clearly outlined in a Letter of Accommodation from the Center for Accessible Learning/Resource Center for Students with Disabilities. Accommodations which each and every person to is entitled to under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which says that every Canadian is entitled to an education. Sometimes it’s a lack of understanding on behalf of the individual on what’s going on in their own body. Sometimes it’s a lack of a diagnosis. Sometimes it’s impossible to get registered with an IST or CAL. Sometimes the teachers don’t follow the accommodations anyway. Yes, the student can go to someone higher up the chain of command, bring in an outside advocate or even pursue legal aid, but when just getting up in the morning feels nearly impossible, sometimes you just can’t find the time, energy, or motivation. Sometimes it’s easier to give up – and that means that our system is broken.

The “Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

“The Charter protects those basic rights and freedoms of all Canadians that are considered essential to preserving Canada as a free and democratic country. It applies to all governments – federal, provincial and territorial – and includes protection of the following: fundamental freedoms, democratic rights […] [and] equality rights for all.” (Government of Canada)

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, “[in] school-age children, reported CAPD [Central Auditory Processing Disorder] prevalence rates range from 0.2% (Nagao et al., 2016) to 2.5% (Schow et al., 2020) to 6.2% (Esplin & Wright, 2014). […] Some pediatric populations demonstrate higher rates of CAPD. Children with attention, cognition, or language disability diagnoses (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, learning disability) are more likely to have a coexisting CAPD diagnosis or have auditory processing differences (Gokula et al., 2019; Maggu & Overath, 2021).”

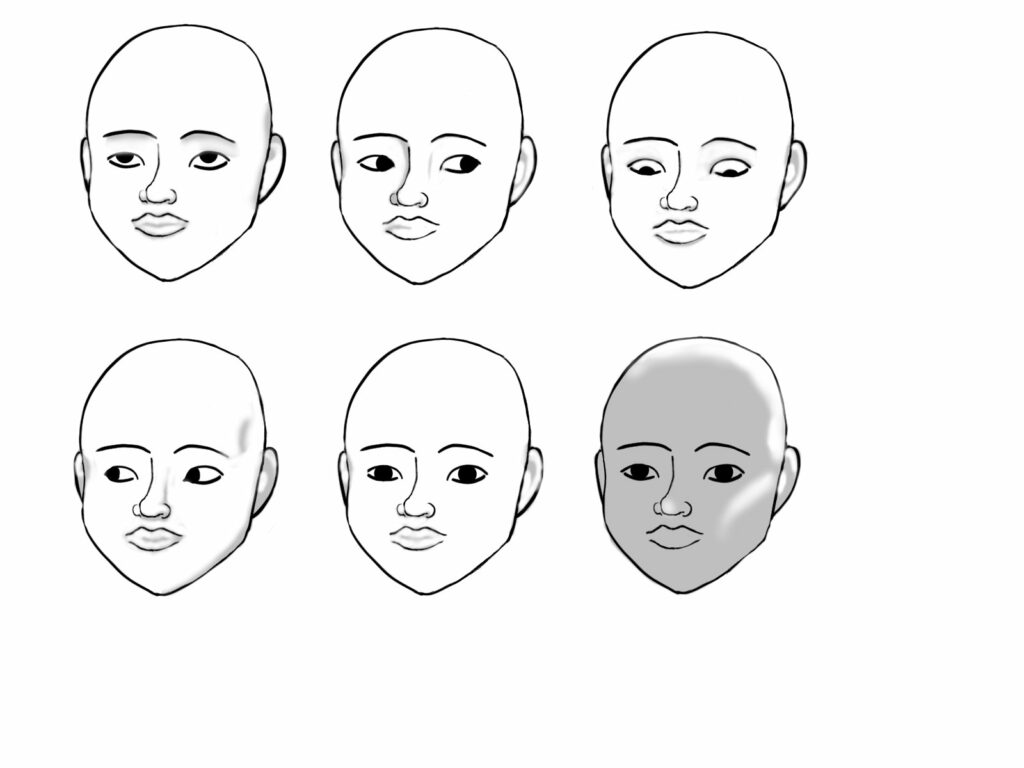

The British Dyslexia Association urges educators to “Use sans serif fonts, such as Arial and Comic Sans, as letters can appear less crowded. Alternatives include Verdana, Tahoma, Century Gothic, Trebuchet, Calibri, Open Sans.” These fonts are much easier for people with dyslexia to read, which improves understanding and engagement.

There is only so much individual educators can do. There are many, many things that could be changed in the way the school system is designed to make it more accessible to students at every level, from providing assistive listening devices, text-to-speech and speech-to-text options on assignments, and streamlining the process of finding accommodations, to simply starting later in the day. One study from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities’ Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement (CAREI) describes the following:

The results from this three-year research study, conducted with over 9,000 students in eight public high schools in three states, reveal that high schools that start at 8:30 AM or later allow for more than 60% of students to obtain at least eight hours of sleep per school night. Teens getting less than eight hours of sleep reported significantly higher depression symptoms, greater use of caffeine, and are at greater risk for making poor choices for substance use. Academic performance outcomes, including grades earned in core subject areas of math, English, science and social studies, plus performance on state and national achievement tests, attendance rates and reduced tardiness show significantly positive improvement with the later start times of 8:35 AM or later. Finally, the number of car crashes for teen drivers from 16 to 18 years of age was significantly reduced by 70% when a school shifted start times from 7:35 AM to 8:55 AM.

Accessibility doesn’t have to look like a complete change in the system. Some changes can benefit the overall student population as well as disabled or neurodivergent individuals, but often times, it just comes down to individuals making an effort. Teachers shouldn’t be expected to know every single way that they could make learning more accessible for every single student. They should be expected to listen, believe, and work with them. Otherwise, we’re left to fight for our rights alone.